RIDE THE TIGER

Colleen Barry and Will St. John

Partners in life, painting, and parenthood, the Brooklyn-based artist’s Colleen Barry and Will St. John will each be sharing a selection of figurative paintings at Caelum Gallery in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, in a joint exhibition hosted by their long-time friends, Adam Driver and Joanne Tucker. The show is titled, Ride the Tiger.

“Art has become overburdened by the impulse to rationalize, theorize, and explicate,” says St. John. “Painting is primarily experienced through the senses and not the intellect. With our work, we are placing sensuality as a value, if not above, then at least equal to intellectualism.”

Things become delightfully tricky when untangling the years of classical training and classical works, deeply imprinted in both artists during a challenging and romantic Italian sojourn, starting in 2012 when St. John accepted a fellowship and residency at the American Academy in Rome. Both artists experienced a culture shock of sorts after crash-landing back in New York at the beginning of what would turn out to be a revolution in American figurative painting. Ride the Tiger is the expression, the fruits, of this obsessive, decade-long journey concerning people and paint, one that would lead both artists, each overburdened with years of accrued skill, back to a place of relaxed urgency, to elicit the painstaking illusion of effortlessness.

“I quickly started forming a resentment against ancient Rome,” says Barry, remembering the sweet bubble of painting nude sculptures in ancient courtyards far removed from the crushing immediacy of the U.S. “There was definitely a cognitive dissonance. Everything we had set up in this classical study didn’t match up with living in New York in the 2010s. The honeymoon of unreality was over. The best painting comes when you realize, ‘I have to live in the world.’ ”

Politically, philosophically, ideologically, and conceptually relevant again is the presence of real-world and more locally, “art world,” darlings in Ride the Tiger, like the actor Hari Nef (a touch of Courbet’s Beautiful Irish Woman, Sargent’s Madame X, and Botticelli’s Venus) and the gallerist and musician, Ruby Zarsky (flourishes of Rembrandt, di Vinci, and Renoir for the texture of both light and lightness), and actress Patricia Black, all of whom are transgender and graciously agreed to pose for St. John. To paint portraits of the living and recognizable, especially those who are often relentlessly advocating (whether willingly or not) for those who might share their experience, is to invite compounded contemporary conversations about representation (the artist in institutional[ized] space, the subject, and the final art object), marginalization, and the connection to intersectional identity. For St. John, contemporary signifiers are important but Ride the Tiger is also synonymous with “a vibe”, something powerful and elusive, natural and exotic, ineffable and true. “Ride the Tiger is less about a coherent conceptual model for the painting,” he says, “and more about an attitude, a flamboyant approach to art and life.”

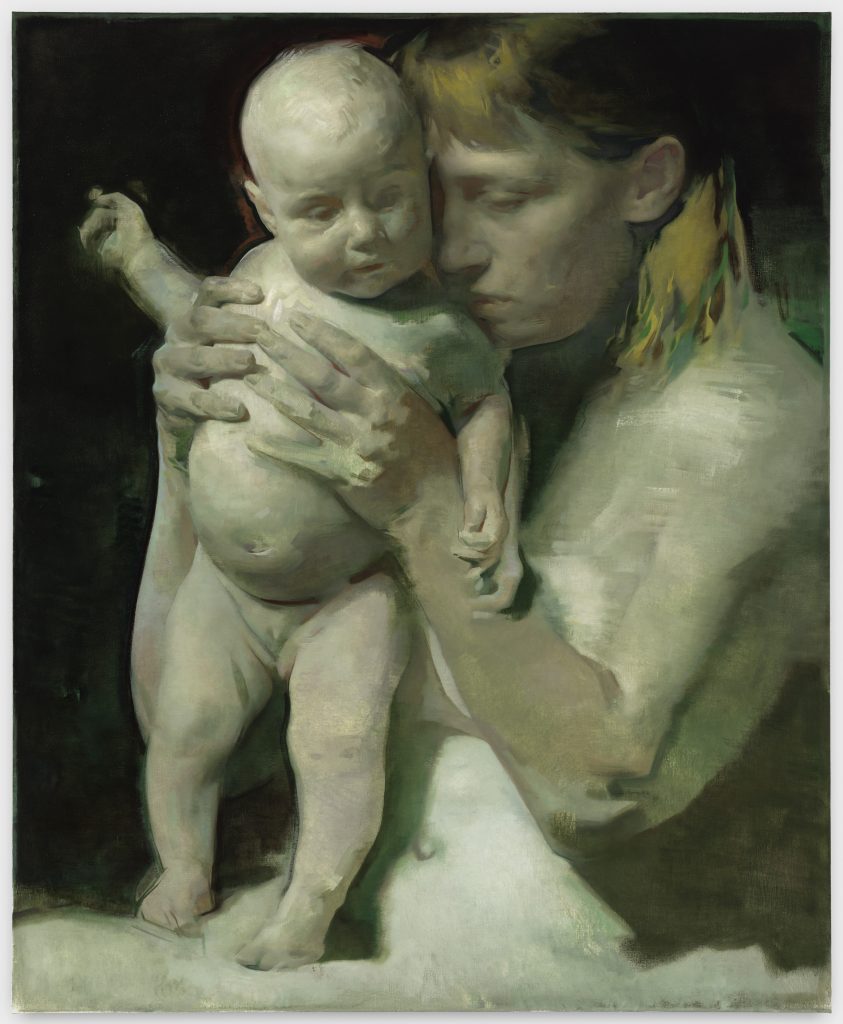

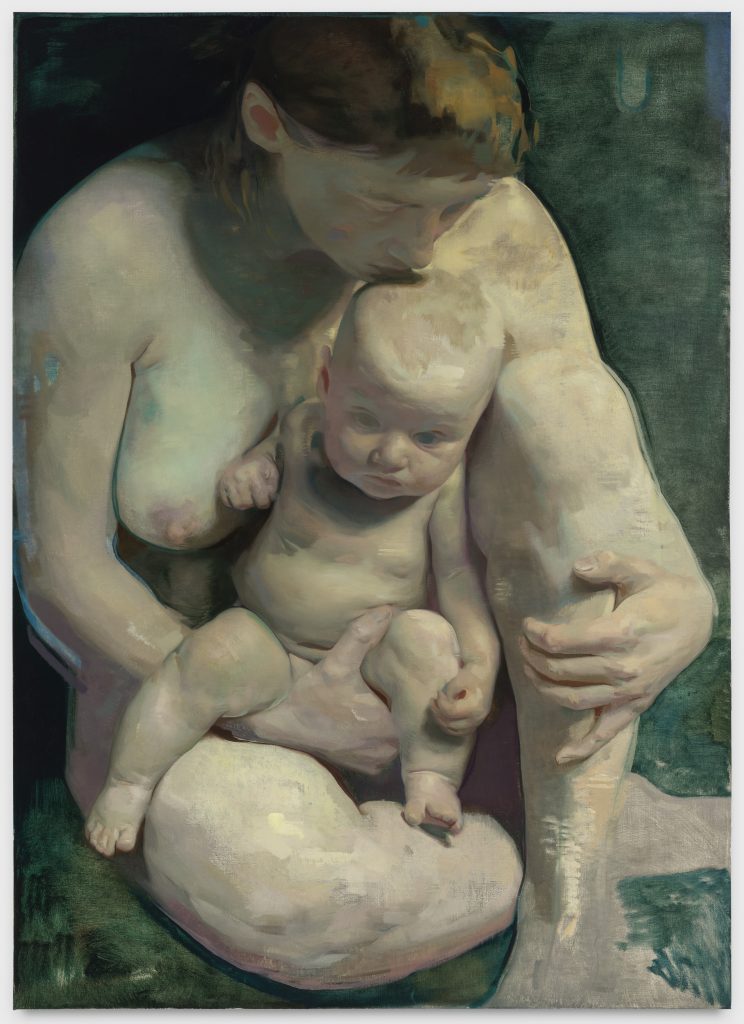

Where St. John’s playful but meticulous portraits refreshingly evoke swirling, jealous whispers of chiaroscuro and naughty tendrils of truffled sfumato, Barry’s works are more sculptural and frustratingly, perhaps almost apologetically personal. These are beautiful, tender, frightening dreams, transformed and rendered up with raw, primal instinct, despite being planned over the course of several evolving studies in various mediums, all built out with consistent architectural and compositional integrity. Richly infused with undimmed childlike curiosity, Barry’s best pieces radiate a subtle, melancholy, neon nostalgia, presented boldly and in the nude, all for intimate public consumption. The brutalist construction, controlled demolition and glorious rebirth of Barry’s paintings betray a hand that knows and desires soft silk and hard stone, the anima and the animus, the white glove and the blue-collar, mother and nymph. Like St. John, there are contemporary hints of Will Cotton and John Currin, but Barry’s hand, especially present in her large-scale work, The Feet Washers (2022), recalls the sensuous hand of Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners, which was unveiled at the Salon in 1857 and was received poorly by upper-class Parisians who felt they were somehow being mocked due to the elevation of three female farm-hands toiling and bending in vast, unforgiving fields.

“A lot of what is happening today in the commercial art world looks exactly like what was happening in the Salon in the 19th century,” says St. John. “There are unintended consequences of closed systems. We see ourselves as artists who would be more comfortable in the Salon des Refusés (Exhibition of the Rejects), despite our painting using these so-called classic materials and techniques and featuring subjects that are actively maneuvering in these same elite social spheres.”

“We’ve always been insiders and outsiders,” says Barry, whose mother (nurse), father (commercial painter), and step-father (electrician and now the school’s theater director) all took, or rather created jobs at the same private high school (Dwight) on the Upper West Side of New York City so she could afford to attend as a rebellious, spiraling teen with the unrepentant soul of an artist who would one day discover that same soul reflected back. Ride the Tiger, an art show hosted by a couple who in parallel worked in and through the creative trenches to emerge in the light, is making an appeal to the insiders and outsiders in all of us.